Which Ancient Philosopher Are You?

31, December 2019 § 2 Comments

Epicureanism. Living gracefully within the garden of nature.

The Aegean Center students and staff spend a month each fall living and studying in the Villa Rospigloisi, in Pistoia, Italy. Besides classes in drawing and photography, we learn about Renaissance art and travel most days to see masterworks, returning with gratitude each evening to our villa in the hills. We often linger in the garden in the hours before dinner, watching the light play over the 400 year old magnolia trees, listening to the fountain splash and enjoying the aroma of food coming from the kitchen. We have few distractions, plenty of time to converse, and delicious home cooked meals. The combination of study and simple living create a joyous and rewarding month.

Our Villa Garden in Tuscany

Our Villa Garden in Tuscany

The fact that we are studying in Italy and Greece compels me to introduce a short conversation about ancient philosophers to my students. To make this interesting we read short synopses of seven different philosophies of the ancient world and see which of these resonates with their ideas of how to live a good life. Through a series of questions most of my students this term decided that they identified with Epicureanism. One student decided he was a nihilist, though that wasn’t on the list, and a few were drawn to Neoplatonism.

Epicurus was a 3rd BCE philosopher who believed that through elimination of fears and desires (ataraxia) people would be free to pursue simple pleasures to which they are naturally drawn. His followers were known as the Garden People and worked to banish superstition and cultivate a rational understanding of nature. Unlike many other philosophical discourses, women were allowed and urged to join his circle. Epicureans felt that discovering simple pleasures and living a prudent life leads to the greatest social happiness, that understanding the power of living within nature’s limits was essential. The word Epicureanism is misunderstood now as advocating hedonism but the philosopher himself said that a person can only be happy and free by living wisely, soberly, and morally. He said, “Nothing is enough for the man for whom enough is too little”. Our intention is to create an arts program with echos of this joyful search for individual happiness. We stress living with few material requirements, eating food prepared with pure ingredients and being in nature. We have no pretensions to luxury and yet we provide a wonderfully rich and fruitful atmosphere in which students can achieve their best . When simple wants are satisfied we have a deeper appreciation for the aesthetics aspects of life, of beauty, of art.

Epicurus

Epicurus

In contrast to my students, I tend toward the Stoic philosophy. Again, modern understanding of this philosophy misinterprets Stoicism as merely censoring strong emotions. Marcus Aurelius and Epitectus elucidate the philosophy of Stoicism as a guide to find peace; integrity being the chief good. Epitectus said, ““Happiness and freedom begin with a clear understanding of one principle: Some things are within our control, and some things are not. It is only after you have faced up to this fundamental rule and learned to distinguish between what you can and can’t control that inner tranquility and outer effectiveness become possible.” What he believed was true education consists in recognizing that each individual has their own will and cannot be compelled or hindered by anything external. He felt that individuals are not responsible for the thoughts that arrive in their consciousnesses though they are completely responsible for the way in which they use them. “Two maxims,” Epictetus wrote, “we must ever bear in mind—that apart from the will there is nothing good or bad, and that we must not try to anticipate or to direct events, but merely to accept them with intelligence.”

Filigree of Wildflowers on Paros

Filigree of Wildflowers on Paros

And, “Wisdom means understanding without any doubt that circumstances do not rise to meet our expectations. Events happen as they may. People behave as they will.” Finding that my ideals on how to live aligned best with the Stoics I also realised it aids my teaching; empowering me to honour each individual‘s place in the hierarchy of learning, reconfirming that competition has never been an effective teaching tool. I also recognise that what I say and what I teach will be taken by each student to mean what they interpret it to be and not always what I have said. Patience and being an attentive listener are paramount in a teacher but Stoicism also illustrates that 14 different students will have 14 different approaches to a given lesson. Each student will need specific help to elicit their best qualities. It’s not about meeting my standards as much as it is about their comprehension. And, of course, a teacher must accept that each group has its own personality. Fortunately in this group, they were mostly Epicureans by nature.

Yellow & Blue Paros Spring

Yellow & Blue Paros Spring

Raphael & 北斎

15, August 2017 § Leave a comment

Raphael’s Drawings: at the Ashmolean & Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave

At the end of the session this last spring John and I traveled to England to spend a few days in Oxford. We went to see a show of Raphael’s drawings at the Ashmolean, a collection of over hundred and twenty of his original works of art. Drawing exhibitions are far and few between and I was particularly anxious to see this one because Raphael’s draftsmanship is extraordinary and difficult to find and see in person.

It has been said that drawing, within the visual arts, holds the position of being closest to pure thought. (Elderfield) In this sense the drawings allow us to see inside Raphael’s mind as he composed images which would evolve into paintings, frescoes and tapestries. His exploratory line and his imaginative thought process are clearly on view in these works. You feel him working through ideas, expressing emotion with a variety of poses and exploring specific narratives. His drawings are derived from models, imagination, and sometimes from memory. What struck me most was the delicacy and fineness of his workmanship, the exquisite details and the accuracy of his line, his potent understanding of how light describes form. I learned that he often used a stylus to sketch out the preliminary form on the paper before beginning the drawing. This was called a blind line because it did not leave a mark. The drawing was then refined with either metal-point, red chalk, or charcoal. Exploring the spiraling tensions and revealing a staggering knowledge of anatomy he amplified the composition with interlocking negative space and groupings of figures. He was able to reveal the emotional quality of the figures with a minimum of information, sometimes showing only the back of a head or a gesture of the hand to communicate the mood. With rhythm, geometry, and poetry of line his drawings become a testament to the human form as an expression of life force.

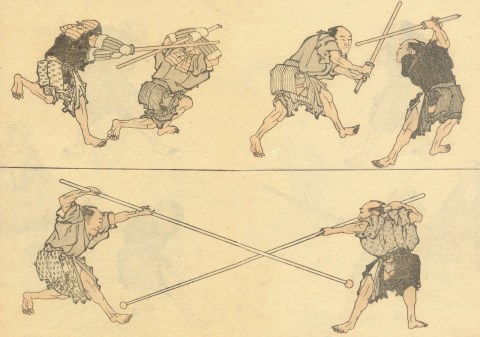

On the way back to Athens we stopped in London and were lucky enough to see the exhibition “Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave” at the British Museum. This artist’s encyclopedic knowledge of nature is on show with many drawings done with ink and brush, woodblock and illustrated books. Again I was struck by the detail and careful renderings, the delicacy of his work. I think it was Ruskin who said that in fine art there must be something “fine” and I thought once again, looking at Hokusai, that perhaps this is something we’re missing in much of contemporary art. It seems that the muscular, the shocking and the mundane have more value to us than careful observation and recording of form which is so lovingly revealed in these masterworks. Although the artists lived two and a half centuries apart and on two different continents, although they depict two different cultures, there are common elements to their work. Both artists express the inexpressible through the twisting forms of human anatomy, pushing to discover at some level our common humanity and our extraordinary capacity to endure. Meticulous, patient observation combined with imagination and the desire to reveal truth is the binding principle that brings these two artists forward into our world with enduring quality.

Jane Morris Pack

Εγκύκλιο Παιδεία • Liberal Arts

3, February 2017 § 2 Comments

“When we ask about the relationship of a liberal education to citizenship, we are asking a question with a long history in the Western philosophical tradition. We are drawing on Socrates’ concept of ‘the examined life,’ on Aristotle’s notions of reflective citizenship, and above all on Greek and Roman Stoic notions of an education that is ‘liberal’ in that it liberates the mind from bondage of habit and custom, producing people who can function with sensitivity and alertness as citizens of the whole world.” –Martha Nussbaum, Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, 1998

Seven Liberal Arts: Francesco Pesellino: 1422-1457 Florence

Seven Liberal Arts: Francesco Pesellino: 1422-1457 Florence

While hoping to find a way to take a much needed sabbatical many years ago I made some phone calls in search for a person to take over my job for a semester. I talked to a woman who taught at a well known academy in the States, someone who I felt could teach drawing and painting simultaneously as I had been doing for years at the Aegean Center. I gave her the outline of the program; a three month course, in Greece, teaching 20 hours a week, covering the gamut from printmaking to oil painting. She brushed aside my inquiry but not because she felt the weight of long hours of teaching, or because the responsibilities were onerous, but because she would need to teach drawing and painting concurrently. She said that a student needed a full year of basic drawing, followed by a full year of figure drawing before they should be allowed to touch a brush. When I explained that being a single semester abroad program prevented us from spreading out the curriculum in this way she dumbfounded me with her response. “Well”‘ she said, “I consider myself a fascist when it comes to art instruction”. I thanked her for her time and promptly hung up.

In relating this story to students I often wondered whether the fascist intent was sanctioned by her academy or if it was just her own perverse mindset. I have unfortunately seen and heard of teachers who felt their method was uniquely correct and had no tolerance for other viewpoints. In art classes the slavish adherence to what is fashionable and a blindness to tradition can narrow students responses. As teachers we must all ensure that our students learn the basic skills that will serve them in future no matter which direction the art world takes. I am deeply committed to obtaining and practicing these skills, but to be a self proclaimed fascist in order to attain that objective is repugnant. Recently I contemplated her response again and thought about it in context to the current political climate. It still horrifies me and I still fight against the dictates that her statement implies.

The Liberal Arts were conceived to educate citizens who could uphold the highest ideals of the Greek and Roman cultures. Rhetoric, grammar, logic comprised the trivium and to these were added the quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. Over the course of the centuries a liberal arts education has come to means something broader but it still indicates a course of study which seeks to inculcate a student to uphold the fundamental underpinning of a democratic society. The arts, especially the visual arts, play a role in embedding memory, culture and history into the minds of citizens. The museum plays its part as well as the galleries, publications and criticism. The arts aspire to imagination, forward thinking, to uphold aesthetic ideals and keep sensitivity alert. This perhaps is why the first thing many dictators do is imprison the artists and poets. But art can also be fashioned into propaganda and can in itself become weighted down with rules and dictates. And apparently teaching art can become fascistic as well.

If we are to remain an open society we need to teach the creative process and embody it as well in our teaching. I try to foster a creative environment in the studio along with emphasizing the discipline that learning an art form demands. Strangely, many art students do not feel creative. The striving to make something of merit often stifles the urge to begin. Creativity requires a certain amount of mess, of boredom, of play and practice in order to perform its magical alchemy. Rigid hierarchical formulae do not help to promote its appearance. We cannot be creative if we are being taught that conforming is the most important requirement. This is why so many students feel that being creative is a rare gift rather than a natural outcome of their nature, too many years spent in graded, monitored, tested classrooms can kill off the ability to create. Often beginning students are intensely creative before fear and compliance knock them back into simply performing for others.

I stay in my job with pleasure, it keeps me involved in my passions and engaged with young clever minds. I teach drawing and painting but I also feel my job is to awaken students to their own nascent creativity. To engage in the creative process is to grow as a person and as a citizen of the world. Within the beautiful environment of the Center with its multicultural milieu, with imaginative and intellectual activities and trusting relationships the creative is allowed to emerge. :Jane Morris Pack

“Those persons, whom nature has endowed with genius and virtue, should be rendered by liberal education worthy to receive, and able to guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens; and . . . they should be called to that charge without regard to wealth, birth or other accidental condition or circumstance.” –Thomas Jefferson, 1779

Annelise Grindheim’s Drama

10, July 2016 § 1 Comment

by: Jeffrey Carson

The origins of drama are mysterious. But my intuition suggests that all drama starts in awe of the world, its powers and unseen powers, its passions and irresolutions. Drama has its roots in religion, cult, magic, poetic rapture, birth/sex/death, and natural wonder. I think this is true of anonymous Passion plays from the Middle Ages, Shakespeare’s investigations of everything human and beyond, ghostly Japanese Noh, rollicking Restoration comedy, throbbing opera, and even the great realist works of the last century-and-a-half, whose master is Henrik Ibsen.

I did not mention ancient Greek plays because these astonishing works – we have thirty-two of them – seem to know this about themselves, and consciously embed themselves in primitive ritual and, with music and poetry, political realism.

The Aegean Center’s drama teacher, Anneliese Grindheim, knows these things, and her love and understanding of the Greek plays informs her work here on Paros. Last autumn she produced a condensed version of Lorca’s frightening tragedy, “The House of Bernarda Alba”, which, in image-loaded verse, shows what happens when society’s rules try to squelch the natural joy and passion of life. Working with small forces – students and a few local friends – Annelise trimmed the work to its essentials – she has an amazing ability to do this with respect and accuracy.

Annalise Grindheim

This spring’s work was even more ambitious. It was Ibsen’s “Lady from the Sea”, a realist drama. Redacting again, Annelise found the poetry and intensity curled deep in the Norwegian master’s realism (she is Norwegian herself). The play is a liminal work, and we are never sure what will happen as the symbols keep being transformed. The actors performed it on the beach, sometimes on sand, sometimes in water. The growth of the heroine’s soul and self into maturity, and its salutary effect on her husband, were aided by movements derived from dance, by declamation derived from poetry, by masks, and by the sea itself – wavelets, gulls, breezes, briny clarity. Liminal indeed.

I’m fortunate to work at the Aegean Center with such skilled practitioners of their arts as John Pack, Jane Pack, Jun-Pierre Shiozawa, and most recently, Annelise Grindheim. What will she come up with next? I may write a poem about it.